Scientists at Imperial College London (ICL) have estimated that 2,300 people died in Europe during the brutal ten-day heatwave in late June and early July.

The researchers also calculated that the effects of climate change tripled the death toll of the disaster, which would have been much milder were it not for the burning of fossil fuels and the consequent increased concentration of heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

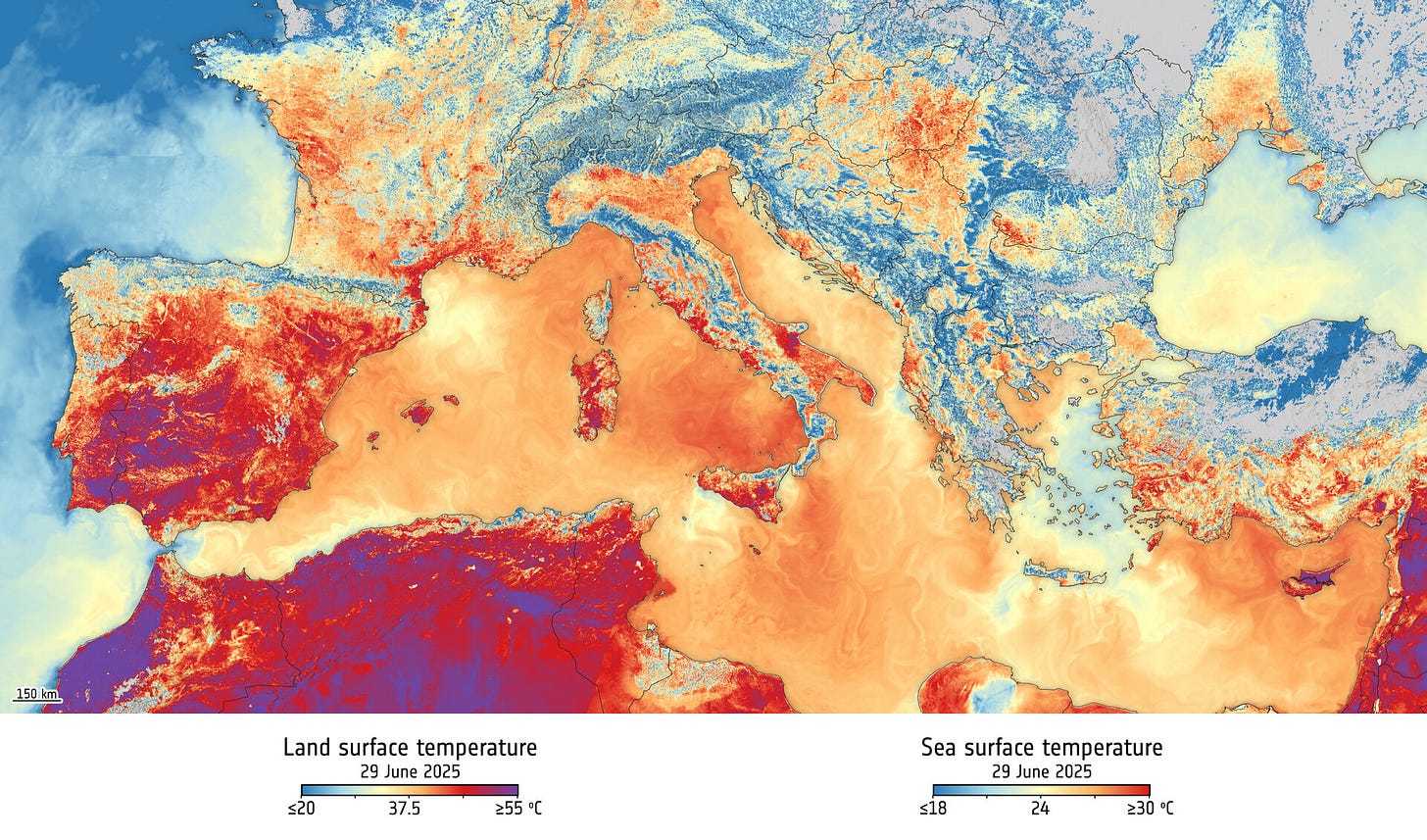

During the event, wildfires erupted throughout the continent as hot and dry air turned woodlands into tinderboxes. The heat also forced mass school closures in France, work bans in Italy and delays on trains (including one carrying your correspondent) due to sagging electric lines.

The effects of the temperature spike were exacerbated by Europe’s relative lack of air conditioning - a technology that effectively cools indoor environments by collecting heat and expelling it to the building’s exterior. Only 20% of households on the continent have A/C, compared to higher than 90% in the United States and Japan and around 60% in China.

This difference is due in part to Europe’s historically mild climate and high energy prices in many countries. But cultural aversion to the artifice of the technology itself is also a factor. For generations Europeans have gently chided visiting American tourists for their attachment to the A/C and the comfort it provides, viewing it as an indulgence.

To A/C or Not to A/C?

This year’s heatwave, however, clearly illustrates that in an era of climate change access to cooling becomes less an issue of comfort or extravagance and more an issue of life or death.

A recent analysis featured in London’s Financial Times demonstrated that death rates skyrocket 100%-150% in major European cities after an extreme heatwave, while in the United States they barely budge. Such starkly disparate numbers have created momentum across the European political spectrum to increase access to air conditioning through subsidies or mandates.

Even more useful, however, would be a concerted effort to install heat pumps across the Vieux Continent. These devices work like air conditioners in summer but are also capable of providing heat in winter. They operate on electricity, which means in addition to keeping Europeans cool they would directly reduce carbon emissions in the heating sector.

Putting a heat pump in 50% of European homes by 2030 would be one of the biggest and most important killing of two birds with one stone in public policy history, marrying tangible public health benefits with Europe’s climate goals. Furthering energy independence (heat pumps are powered by locally generated electricity and often made in Europe) would be an added bonus. Such a policy should be immediately adopted by the EU, Britain and all other European countries.

The grim trajectory of the Earth’s climate means inaction is not an option. The deadly summer of 2025 will be one of the coolest we experience in our lifetimes. The pleasant not-too-warm summers of our childhoods are gone forever - a vanished country to whose bourn no traveller may return.